Political predictions are a dangerous business, especially this year. But it does look as though one way or another, the U.S. Senate will vote to confirm the nomination of Judge Neil Gorsuch to the U.S. Supreme Court. The open question is how much damage Democrats will do to their own long game in the process.

The long game is this: confirming Gorsuch will not change the overall liberal-conservative balance on the Supreme Court. But two of the current sitting justices are over 80, and a third is nearly 79. These three are considerably less conservative than Justice Antonin Scalia, whose death created the vacancy that Gorsuch has been nominated to fill.

So if any of these three justices were to retire in the next four years, or perhaps eight, President Donald Trump would have the opportunity to nominate a conservative justice to replace a liberal or centrist justice, and the balance of the nation's highest court would be dramatically tipped to the right.

In short, the next confirmation fight will be Armageddon. And if Democrats have a weak hand this time, they could have a much weaker one next time if political pressure from the Democrats' left flank succeeds in forcing the abolition of the filibuster.

More on this in a moment. But first, let's take a look at this week's Senate Judiciary Committee hearings on the Gorsuch nomination.

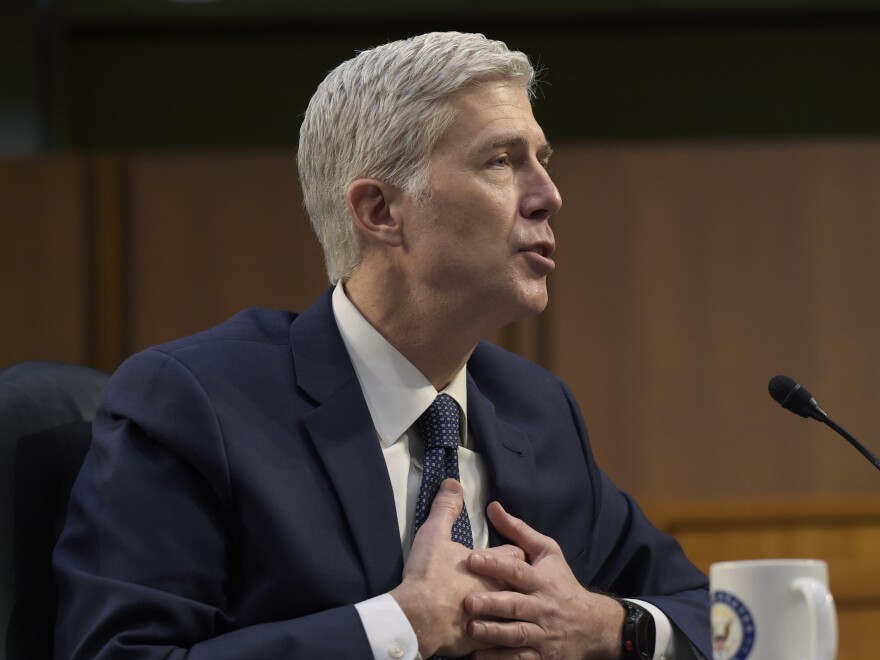

A rehearsed performance at the confirmation hearing

The judge emerged from more than 20 hours of questioning largely unscathed. His performance was skilled and schooled. He looked the part of a distinguished, white-haired but youthful, judge, and projected an image of dispassionate judicial neutrality to the point of chilliness.

The old adage is that the secret to spontaneity is to know how to fake it. And spontaneity was the one score on which Gorsuch may have rated a less than stellar grade. He was so practiced in his answers that even his obviously planned jokes fell flat.

Indeed, his desire to avoid committing himself to any substantive answer, even about longstanding and popular Supreme Court decisions, almost trapped him into refusing to strongly endorse Brown v. Board of Education, the 1954 decision declaring segregated schools unconstitutional.

His initial answer may have been dodgy because he was tired at hour nine of what ended up being an almost 12-hour day of testimony. But whatever the reason, Gorsuch finally woke up and realized he was taking the principle of hedging too far.

When pressed by Democratic Sen. Richard Blumenthal of Connecticut, Gorsuch asserted that Brown "corrected a badly erroneous decision," referring to the separate-but-equal ruling in Plessy v. Ferguson.

"It's one of the great stains of the Supreme Court's history that it took it so long to get to that decision," Gorsuch said.

That said, he continued to hedge when asked whether he thought the Court ruled correctly in two decisions issued roughly fifty years ago that declared unconstitutional state laws that made it a crime to distribute or provide medical advice on birth control. In contrast, Blumenthal told Gorsuch, the last two Republican Supreme Court nominees, John Roberts and Samuel Alito, directly answered that question and said they agreed with the result.

" You have been ... able to avoid specificity like no one I have ever seen before, added a frustrated Democratic Sen. Dianne Feinstein of California.

Tough questions from the Democratic Senators

The Senators on the left sought repeatedly to portray Gorsuch as a tool of corporate America who had no sympathy for the little guy. Exhibit A in that effort was the so-called case of the frozen trucker.

A commercial truck driver named Alphonse Maddin was driving his trailer truck through Illinois when the brakes on the trailer froze. Maddin pulled over, reported the problem to his employer, TransAm Trucking, and was told to wait for help.

After waiting three hours in sub-zero temperatures with no heat working in the cab, he could no longer feel his legs and was having trouble breathing. So he unhitched the trailer from the cab and drove to a service station for help, returning after about 15 minutes when he finally heard servicemen were on the way. He was fired for abandoning the trailer.

Maddin sued under a federal law that protects whistleblowers from being fired for refusing to operate an unsafe vehicle. He won at every level, including before an appeals court panel. Judge Gorsuch was the lone dissenter, writing that Maddin "was fired only after" he declined to take the action protected by law "and chose instead to operate his vehicle in a manner he thought wise but his employer did not."

Democratic Sen. Al Franken of Minnesota called Gorsuch's dissenting opinion "absurd" in view of the fact that if the trucker hadn't left the trailer behind while he drove away to get help, he would either have risked "dying" from the cold himself by staying put, or risked the lives of innocent motorists by driving the trailer with the frozen brakes on to the highway.

Gorsuch said he "totally empathized" with Maddin, but otherwise dodged questions on the case.

The nominee did suffer one embarrassment when a decision he wrote limiting the rights of disabled children in public school was for all practical purposes unanimously reversed by the Supreme Court — at the very hour Gorsuch was discussing this at his hearing. He defended the decision, saying that he was bound at the time by the precedent of his appeals court, and that in light of the Supreme Court's ruling, he had been "wrong" and was "sorry."

The frozen trucker case and the disabled kids case caused Democratic Sen. Dick Durbin of Illinois to lament that he was having difficulty finding evidence of a "beating heart" in Gorsuch's jurisprudence.

Gorsuch responded by citing a half dozen cases in which he had ruled "for the little guy." More to the point, he said, while his dissenting opinion in the frozen trucker case may have been "unkind," it was required by law, and the job of a judge, he said, is to be faithful to the law.

He did have some Gary Cooper moments that left his inquisitors empty-handed. Democratic Sen. Sheldon Whitehouse of Rhode Island sought repeatedly to get a fix on the nominee's views about campaign finance laws. Noting that recent Supreme Court decisions have opened politics to an unprecedented "flood of cash," Whitehouse worried about the ability of big money to capture Congress, federal agencies, and even the Supreme Court.

You could almost hear the guns on his hips clanking as Gorsuch, flinty-eyed, replied: "Nobody will capture me."

After the second long day of testimony was over, Gorsuch stayed in the hearing room to greet friends and supporters. It looked much like a celebration without drinks.

The minority party's political quagmire

On Thursday, Senate Minority Leader Chuck Schumer announced that he would lead a filibuster.

Democratic sources saw the move as an attempt by Schumer to shore up a weak hand. A few numbers are instructive here: It takes 60 votes to end a filibuster, meaning 60 votes to cut off debate and move to an up-or-down vote on a Supreme Court nomination. There are 52 Republican senators, a majority, but they would need the votes of eight Democrats to cut off debate.

It would be one thing if this were an unchangeable rule. The Democrats could hold up the Gorsuch nomination forever—something that in their heart of hearts they would love to do. They remain white-hot furious over the GOP refusal for almost a year to give even a hearing to Judge Merrick Garland, President Barack Obama's Supreme Court nominee to fill the Scalia seat.

Although Democrats refer to the open Supreme Court seat as one that was "stolen" from them, most Senators are political pros.

They know that if they are able to block the Gorsuch nomination with a filibuster, Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell will almost certainly launch the so-called "nuclear option." McConnell and other more centrist Republicans like Sen. John McCain of Arizona and Sen. Lindsey Graham of South Carolina have made clear they will change the 60-vote rule for cutting off debate if need be.

The majority party can change the rules with a majority vote, and thereafter, it will only take 51 senators to move to an up-or-down vote on a Supreme Court nomination. Gorsuch would sail through with at least the 52 Republican Senators voting for him, and the filibuster option would be gone. If there is a political Armageddon, the Democrats would have disarmed themselves—wasting a fight over the filibuster on a nominee who already seems to be guaranteed confirmation.

The problem is that even though senators can easily game out this scenario, their Democratic base is leaning on them, hard, to do something—anything—to stop Gorsuch, even though it is a hopeless cause.

The Gorsuch nomination could even mark the last tiny gasp of bipartisanship on Supreme Court nominations. The failed Robert Bork nomination in 1987 was defeated by 58 senators, including six Republicans. Consensus seemed to rebound when the Republican nomination of Anthony Kennedy was confirmed 97-to-0 and David Souter in a 90-to-9 vote.

In between, a Democratic-controlled Senate confirmed Republican nominee Clarence Thomas by a narrow 52-to-48 vote. But after that, Democratic nominees Ruth Bader Ginsburg and Stephen Breyer were confirmed by votes of 96-to-3 and 87-to-9, respectively.

Eleven years passed before there were vacancies again. Nominated by Republican President George W. Bush in 2005, John Roberts was confirmed as chief justice by a Republican-controlled Senate, but he managed to get the votes of half the Democrats. In 2006, Bush nominee Samuel Alito got only four Democratic votes. In 2009 and 2010, President Obama's nominees Sonia Sotomayor and Elena Kagan were confirmed with 9 Republican votes and 5 Republican votes, respectively.

Ultimately, President Trump will get his Gorsuch nominee through the Senate, but only because his party has a majority there.

As conservative Ed Whelan, President of the Ethics and Public Policy Center, observes, the "underlying politics have shifted" on judicial nominations and confirmations. Formerly, if a nominee had stellar legal and character credentials, most senators would defer to the President's choice.

But now, he says, "the political bases on both sides have driven their senators to explore and oppose nominees based on judicial philosophy."

Intern Lauren Russell contributed to this report.

Copyright 2021 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.