On a mild Saturday morning in early October, I pulled on my rubber rain boots and trekked down past the tree line while kids played soccer.

Members of a volunteer group called Friends of Brandywine Springs surveyed the remains of a historic spring and tried to find the base of another one.

"The actual spring level is probably about three feet down from where the road level is, so we have a feeling we’re gonna have to go down here maybe three or four feet before we actually maybe hit some sort of foundation," said volunteer Ed Lipka. “I’ve been a member of Friends of Brandywine Springs since 1994. We’ve been digging since April of 1994.”

Yes, Lipka and his partners have spent 20-years excavating an old amusement park that occupied the area in the late 1800s and early 1900s.

“Mostly we just pick the second Saturday of the month, sometimes if it’s raining or too muddy to dig we do all our measurements and Mike goes and uses his CAD engineering drawing and is able to put some concepts together based on what we find," Lipka said.

That second Saturday of October didn’t yield many findings, but they did find at least one thing.

“That’s a soft drink bottle," Lipka said. It almost looks like the old Pepsi bottles.”

The volunteers were slightly disappointed to discover the Cloverdale bottle wasn’t manufactured in Delaware, but instead in Baltimore.

And since rain was in the forecast, Friends of Brandywine Springs President Mike Ciosek had limited plans for that October dig.

They focused on gathering some measurements instead. Ciosek and Lipka took measurements of a datum point – a starting point or point of reference from which all other measurements are taken.

Lipka held up a big measuring stick – like a giant yardstick – at the datum point while Ciosek used a telescope of sorts to compare the height to areas of the spring excavation site.

Over the years, the volunteer group has used archeological techniques like the datum point to identify the corners of different amusement park structures: rides, theaters, pavilions and more.

With the help of photos and historical descriptions of each site, they use colorful markers to lay out the corners.

It all started in the 1990s with the search for park’s elaborate entrance archway.

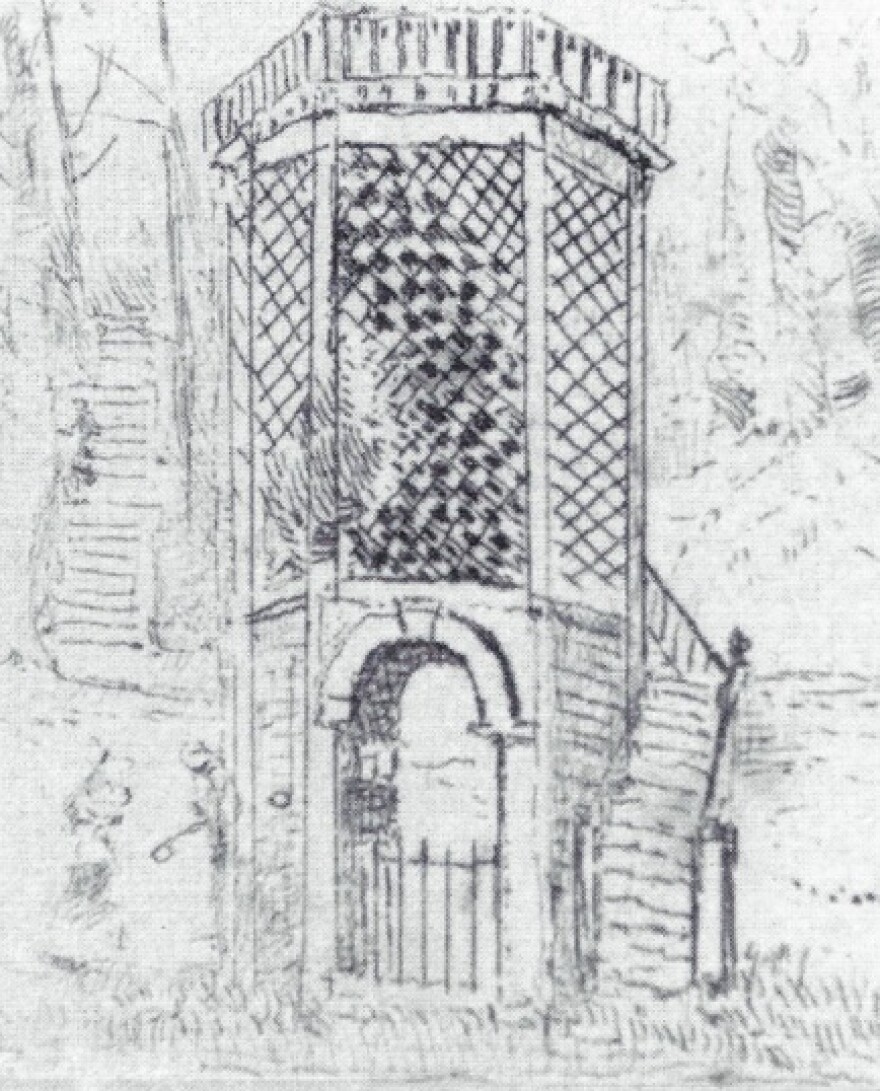

"If you look at a picture of this gothic entranceway, it looks like it has sculpture on it, but it’s just painted, festooned with electric lights," archeologist Keith Doms said.

Doms was one of the first professional archeologists involved in the excavation of the historic amusement park. He says the park’s novelty appealed to him.

"I've learned about Native Americans, I've learned about Colonial," Doms said. "But who has ever excavated an amusement park?"

"That’s one of the reasons why I wanted to get involved," Doms said. "As an archeologist, I’ve learned about Native Americans, I’ve learned about Colonial, but who has ever excavated an amusement park?"

He calls the volunteers avocational archeologists and started teaching them different techniques - like a test unit - to help find structures like the entrance archway.

"A test unit is what an archeologist calls the square that we excavate," Doms said. "Some people call them test units, test pits, test squares.

He said at first, they weren’t successful.

"Next year came around but we didn’t find any evidence of a structure," Doms said. "We found tantalizing artifacts, we found hard-packed gravel. We found fragments of souvenirs – little bits of ceramic tchotchkes that you used to be able to get at the park. So we knew we were at the right level, we just hadn’t hit it."

But they soon had a clue – trolley tracks.

"We actually found – you could actually see the stains of the trolley tracks, you could see where the ties were and where the rails once were," Doms said. "So we knew the trolley line came through there, we knew the archway had to be to the west of that."

They finally found the base of the sign, along with remnants of the electric lights that would have adorned it.

"This is long before rural electrification," Doms said. "If you were in Wilmington, you had electric trolley cars, you had electric lights. But if you moved out into the countryside people were still using Kerosene lamps. But here – at the end of the trolley line – was Brandywine Springs. And at night, the whole valley would be lit up and there’d be a glow that most of these farmers had never seen before."

After the electric sign, the Friends of Brandywine Springs group – with the help of archeologists like Doms – excavated other park sites, like the Ladies Pavilion and the Exhibit Hall.

"Through probing, mapping and some very good guesswork they started finding foundations of various buildings," Doms said. "And once they found a corner, they then would jump over and try to find another corner."

But not all of the structures were that difficult to identify.

"The Katzenjammer castle – which was the most substantial building they built – you could actually see the tops of the blocks sticking up out of the ground, the pillars from the pool hall I think one or two were visible, I think the rest were one or two inches below soil," Doms said.

The Katzenjammer Castle was called the Dreamland in a circa 1911 postcard.

"It was like a funhouse," Doms said.

Barb Silber, another archeologist and one of Doms’ archeology students at the University of Delaware, helped restore another part of the park: Lake Washington.

"It's nice to have a project where there's been a lot of different pieces of research," Silber said. "And they overlap but they don't overlap. So everybody gets a piece to figure out a new piece of the puzzle."

"It’s nice to have a project where there’s been a lot of different pieces of research," Silber said. "And they overlap but they don’t overlap. So everybody gets a piece to figure out a new piece of the puzzle."

She said at the time she started working on the lake project, there wasn’t much water.

"A little swampy, a little marshy," Silber said. "There really wasn’t any water because it had been trained for around 60 years."

But in the park’s heyday, the lake was a scenic abode – similar to something you might see in Central Park today.

“They had these little islands in the middle, with a little pavilion and little grottos so you could take your little sweetie out there, row your boat and have a nice Sunday afternoon part of the park," she said.

Doms was also involved with this project.

"People have no idea that their grandparents used to go out on rowboats and early roller coasters and ask very much like teenagers do today," Doms said.

And even though the park was supposed to be dry – with no alcohol allowed – they found evidence those rules weren’t always obeyed.

"We found whiskey bottles that were not allowed that were obviously dropped overboard, a woman’s hat pin," Doms said.

Many items found during the digs and excavation work - from women’s combs to brass rings - have been preserved by longtime volunteer Melvin Schoenbeck who met me at the museum at Greenbank Station where the artifacts are displayed.

Beer and soda bottles dominate the collection, joined by china Schoenbeck says is actually Japanese pottery. Additionally, there were many coins and lots of glasswork Schoenbeck has super glued back together.

"We very seldom find all of the pieces of anything, but sometimes we find most of them," Schoenbeck said.

The collection also includes a glass gun.

"I hadn’t seen a glass gun before, but when I was a little kid for Christmas one time I got a glass racer and they’re hollow and they’d have a cork stopper and they’d be filled with little hard candies and then after you ate the candy you’d have a toy," Schoenbeck said.

But another gun was used to shoot at some cast iron birds in the museum’s collection.

"Those cast iron birds, they're from the shooting gallery," Schoenbeck said. "They were probably on a conveying device, so they'd go across. They shot at those with 22 caliber rifles. Can you imagine that today?"

"Those cast iron birds, they’re from the shooting gallery," Schoenbeck said. "They were probably on a conveying device, so they’d go across. They shot at those with 22 caliber rifles. Can you imagine that today?"

Shoenbeck says he enjoys putting pieces of artifacts together, just like a puzzle.

"I just – I got hooked," he said. "I just enjoyed it immensely."

And his proximity to the park helped spark his curiosity.

"When we first lived here, we lived just maybe a quarter of a mile away from there and we used to take my daughter over there to play," he said. "I remember what the kids thought was the Indian grave, which turned out to be the Chalybeate Springs."

It’s this site the group focused on during my October visit.

The spring’s iron railings were always visible above ground – contributing to the initial idea of the Indian grave.

But over the last couple of years, the Friends of Brandywine Springs have worked to dig down to the base of the historic spring site.

The county also hired archeologist Bill Liebeknecht to build a retaining wall to prevent what they presumed were soils from the hillside sliding down and covering up the spring site.

But after consulting with the Friends group and others, Liebeknecht discovered it was actually flood deposits from a couple major floods that swept through the area that covered up the spring.

"Mike came in, and he brought his data in," Liebeknecht said. "We sat down and discussed it, went back and forth. They had their interpretations and we had ours. It’s always like that. You can put five archeologists in a room and get six different interpretations."

Liebeknecht is putting together a report on the project which he plans to complete soon.

"You can put five archeologists in a room and get six different interpretations," Liebeknecht said.

But the Brandywine Springs Friends group’s work is not complete, and according to president Mike Ciosek – never will be.

Back at the spring site during the group’s October dig, Mike’s doing some dirty work to make sure he gets the measurements he needs.

"I’m going to get wet, I’m going in for a swim," Ciosek said. "That water doesn’t look too, appetizing. Well this is Chalybeate Spring water, it’ll make you healthy."

He’s using a boat’s sump pump to drain water out of the spring. The draining is all part of a larger plan.

“What I’m trying to do is I’m trying to make a drawing – a cross section –as if you cut this thing right down here and looked at it from the side so I can put this all together in some meaningful way," he said. "But right now, I’m not sure where everything fits.”

With the help of geologists and archeologists like Liebeknecht, several different layers of stone – Chester Park nice, marble and limestone – were discovered near the site, complicating Mike’s original depiction.

"When we broke through this mortar, we found another set of stones underneath and went, oh my gracious!" Ciosek said.

But the spring is now operational, pumping about a gallon of water every minute into the nearby creek.

And eventually, with New Castle County’s assistance, the plan is to create a Victorian-esque lattice-covered gazebo around the historic spring site similar to its original one – complete with picnic tables nearby for afternoon park picnickers – and Pokemon Go players, and to entice residents to explore the park’s many historical markers.

Of all things, Pokemon Go has drawn people to the area. While we were down there the last time, Mike and I, there was several young kids with their parents going through the park and they’re going, oh we never knew this was here, this is great.

I also saw Pokemon Go players on my first visit to the site, and supposedly some of the park’s features are Poke stops.

The group’s next gig is scheduled for the second Saturday in November, and then they’ll take a break before resuming work next spring.